It is important to show the ancestry of the Cherokee, Rachel Fisher, so it is clear the records of the Cherokee Nation can always be used to expose a fraudulent or fabricated ancestry like that of Pleasant Cumiford.

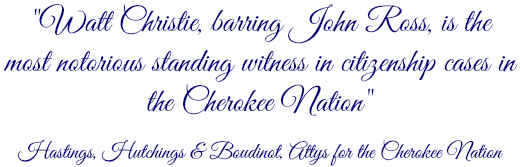

Watt Christie never mentioned the name of the mother of Rachel. He mentioned Rachel and Fisher, her father. He said Rachel should be found on the roll of 1852 and Fisher should be found on the roll of 1835. But what of Rachel's mother? Christie said Rachel's parents lived together near Turnip Town on the Ellijay and that they went to Indian Territory with the Emigration, but he never gave the mother's name. So who was Rachel's mother?

According to the Eastern Cherokee Applications of Fisher's grandchildren, his wife was Polly Fisher, no maiden name given.

While I don't think anyone has ever found definitive proof that identifies Polly Fisher's parents, there is a lot of circumstantial evidence that suggests she was the daughter of Lacy and/or Betsy Christie and at least a half sister to Watt Christie.

In her Eastern Cherokee application, Watt Christie's daughter, Quaitsy (Betsy) Wolf, listed a Polly Fisher as an aunt on her father's side.

In her Eastern Cherokee application, Watt Christie's niece, Polly Ross, daughter of Arley Christie Grease, listed Polly Wa-gi-gu as a 1/2 aunt. Wa-gi-gu connects this aunt to her mother's side.

Quaitsy Wolf and Mary Manus were siblings. Polly Ross was their first cousin. Quaitsy and Polly both reported a child of their grandparents, Lacy and/or Betsy Christie, named Polly. This means Quaitsy identified Polly Fisher as a sibling to her father, Watt Christie, and Polly Ross identified Polly Wa-gi-gu as a 1/2 sister to her mother, Arley Christie Grease/Greece. Watt and Arley were siblings and the children of Lacy and Betsy Christie. This information, in a family tree form, would look like the diagram below.

In order to avoid making the mistake of same name/different person, it is important to do an exhaustive search for information, extract the facts and then evaluate those facts to see if a conclusion can be formed as to whether Polly Fisher, sister to Watt and daughter to Lacy and/or Betsy Christie is the same Polly Fisher who was the wife of Fisher and mother of Rachel.

Watt Christie testified that Rachel's parents lived near Turnip Town on the Ellijay in the Old Cherokee Nation. This is true, per the 1835 Valuations and the 1838 Claims before Emigration, made in the name of Rachel's father as Hatchet. Lacy Christie was also living in the same area. This area was mountainous and travel was difficult (Hill), therefore, the Cherokees who lived in this region were fairly secluded from other Cherokee communities. There were only 38 families living on the Ellijay in 1835. Considering the topography of this region, and the fact not all who lived in the area would be single and marrying age, there would likely only be a small group of women available for Fisher to marry. Based on the approximate birth year of their son,Watt, it is possible Lacy and/or Betsy Christie's daughter, Polly Wa-gi-gu, was the right age to have been the wife of Fisher.

In Cherokee records from 1835 through 1851, the Fisher family is always found living near Lacy Christie and other members of his family. Fisher and Lacy Christie were even in the same detachment on the Trail of Tears. While this doesn't prove there is a familial connection between Fisher and Lacy, it suggests the possibility of one. Until the upheaval caused by the Civil War, it was quite common to find large, extended members of a Cherokee family living in close proximity to one another.

While there is no record of Fisher's wife's death, documentation indicates she probably died before 1860, possibly as early as 1850. Polly's youngest child, born sometime between 1850-54, had no knowledge of her mother which suggests the child was quite young when Polly died. Additionally, prior to 1860, the Fisher surname was virtually unheard of in the Cherokee Nation. While there were Kingfishers, I've found no Fishers, specifically Fisher, on any rolls of the Cherokee Nation until the Drennen Roll of 1851-52. This roll had only one person named Fisher and he was the father of Rachel Fisher. Time and proximity make it highly likely the daughter of Lacy and/or Betsy Christie referred to as Polly Fisher by Quaitsy Wolf had a connection to Fisher. During the time frame in which Polly Wa-gi-gu appears to have lived, there were no other Fishers in the same area as the Christies.

Is all of this circumstantial evidence? Yes. Does that mean it leads us to make the wrong conclusion? No. The evidence and documentation allows a strong argument to be made that the Polly Fisher mentioned by Quaitsy Wolf and the Polly Wa-gi-gu mentioned by Polly Ross was the same Polly who was the wife of Fisher.

Consider these facts:

- Watt Christie knew a lot about the Fisher family.

- Watt Christie claimed kinship to the Fisher family.

- The Fisher family lived near Lacy Christie in 1835 - Turnip Town/Ellijay.

- The Fisher family lived near Lacy Christie in 1838 - Ellijay/Ellijay Town

- The topography of the Ellijay area caused the Cherokees there to be secluded from other Cherokee communities, therefore limiting the pool of possible choices for a spouse for both Fisher and Polly Wa-gi-gu.

- Fisher and Lacy Christie removed with the same detachment.

- After the Trail of Tears, Fisher and Lacy Christie settled in the same area.

- The Fisher family is found living among many from the Christie family on the Drennen Roll.

- #563 - Lacy Christie

- #564 - Arch Christie

- #566 - Katy/Caty Christie

- #568 - Fisher

- #576 - Arley Christie

- The Fisher surname was virtually nonexistent among the Cherokees before the Civil War.

- Cherokee naming conventions suggest that if Polly Wa-gi-gu married Fisher, she would have taken his given name as her surname, thus becoming Polly Fisher, to represent "Polly, wife of Fisher".

While Pleasant Cumiford may have gone to his grave believing he pulled off his con against the Cherokee Nation, he couldn't foresee that, with the passage of time, more information would become available and allow his deception to be discovered. Slowly, through this series on standing witnesses, we have been peeling back the layers of lies to uncover the truth. We haven't just looked at Cumiford's family to show he fabricated a Cherokee ancestry. We've also looked at the family Cumiford claimed, the Cherokee Fishers. In stark contrast to Cumiford's non-Indian ancestry, we find the Fishers repeatedly in Cherokee records, which attests to the fact no fraudulent claim to Cherokee ancestry will be able to withstand the scrutiny of a thorough examination of documents and records.

This isn't the end of Polly Fisher's story. Stay tuned for the next installment in this series where the fabricated ancestry, created by Pleasant Cumiford and Watt Christie, continues to collapse under the weight of the true story of Rachel Fisher and her family.

Those are my thoughts for today.

Thanks for reading.

copyright 2014, Polly's Granddaughter - TCB

Tweet