According to the Identity Theft Resource Center, ghosting is "pretending to be a deceased individual for monetary gain." Fifty-nine years after his death, Young Wolf, also known as Gardiner Green, was figuratively stolen from his grave, propped up in a family tree, and ghosted, but in a different way than we see today. Instead of stealing his identity for themselves, a family stole his identity and exchanged it for the identity of their long dead grandfather in a way that might bring them personal gain.

In 1896, a Congressional Act made it possible for people not recognized as citizens of the Cherokee Nation (and the other four "Civilized Tribes") to apply to the Dawes Commission for citizenship in the Nation. The Commission then began receiving letters from all over the United States asking how people could "get on the rolls" and "get Indian land." A letter, dated July 8, 1896, with the instructions on how to apply for citizenship was published in newspapers all over the U.S.

|

| Muskogee Phoenix, July 16, 1896 |

According to Kent Carter's The Dawes Commission and the Allotment of the Five Civilized Tribes, 1893 - 1914, applications poured into the Commission and "...there were thousands of people who were very interested in the citizenship process; the July 8 circular produced a tidal wave of paper that overwhelmed the commission's three clerks. Many local lawyers had application blanks printed and charged their clients whatever they could to present them to the commission. In a classic understatement, [one commissioner] reported that the amount of "work has exceeded all expectations" and required "an immense amount of clerical work in correspondence, filing papers, numbering and indexing cases, and putting in form for permanent record and preservation all the proceedings pertaining to each case.""

In simple terms, there were a lot of people trying to gain citizenship in the Five Civilized Tribes, many more than anyone expected, and it was nearly impossible to process all of the applications by the deadlines set by Congress.

One of the cases, Squire Green et al, was for the Green family of Missouri with most of the applicants living in Boone County. Their case included no evidence other than notarized statements by family members who swore their ancestor, Gardner Green, was on the 1835 Census of the Cherokee Nation.

One testimony, the first in the long file, claimed Gardner Green was the son of Benjamin Green and brother of James Green, the ancestor of all the claimants. It is unclear how this witness, TBH Green, is connected to the Green family of Missouri, but he insists they are his relation and that he knew Benjamin Shadrick Green, who was a Cherokee Indian. His testimony has the characteristics of those given by professional witnesses (paid witnesses who testified to whatever one wanted in a citizenship case.)

|

| Squire Green et al, 1896 Citizenship application |

|

| Squire Green et al, 1896 Citizenship application |

If this testimony were true (it's not), the Greens would not have been eligible because one had to be a direct descendant of a Cherokee.

The remainder of the applications, if any written testimony was given, suggested Gardner Green was the father of Benjamin Green who was the father of James Green, the ancestor of all the claimants.

|

| Squire Green et al, 1896 Citizenship application |

Every applicant claimed they were "Cherokee Indian by blood deriving the same from" Gardner Green who lived on Rockey Creek, Murray County, in the state of Georgia.

|

| Squire Green et al, 1896 Citizenship application |

There were 29 applications for approximately one hundred people. Those applications were filed by:

|

| Names in red are the purported great grandchildren of Young Wolf, aka Gardiner Green |

Their family tree from Gardner Green to the five living children of James Green that filed applications in 1896 (there were others living who did not file) would look like this:

There was only one Gardner Green listed on the 1835 Census of the Cherokee Nation. That man was Young Wolf, son of Mouse. As explained in this post, he was born in 1809 and was, at most, 28 years old when he died in 1837. He only had two heirs when he died, his wife, Aley, and his son, Ooahhusky who was born c. 1831.

In order for the Green family claimants to have been descendants of the "Gardner Green" on the 1835 roll, they would have had to descend through Young Wolf's only child, Ooahhusky. If the claim the Greens made was factual, then Ooahhusky would have been the father of James and the grandfather of Nancy, Squire, Louisa, Eli, and Margret. As you can see by the dates, the claim cannot be true.

Ooahhusky was born two years AFTER Nancy Green, his purported granddaughter, and one year before Squire Green, his purported grandson. He was born 42 years AFTER his purported son, James Green, was born. It is physically impossible for Ooahhusky to have been the father of James or grandfather of Nancy, Squire, Eli, Louisa, and Margret. None of these Green claimants descended from Ooahhusky or Young Wolf, aka Gardiner Green.

So how did the Green claimants know "Gardner Green" was on the 1835 roll if they did not descend from him? It's simple. They, or someone they knew, looked at the roll and noticed there was a Green on it. There were copies of the 1835 roll available for people to review. Thomas Skaggs, the notary public on nearly all of the 1896 claims the Green family filed, was also a claimant for citizenship in 1896, but through a different Cherokee. In a letter he wrote to Guion Miller years later, Skaggs said he was the one who found out about the "...Gardner Green decendants being entitled."

|

| Eastern Cherokee Application, Thomas M. Skaggs, 36571 |

Also, on an Eastern Cherokee application filed years later by Green claimant, Martha Rosana Brown, the applicant wrote "gardner greens name is on page 188th of the roll 1835 taken in the state of georgia" in a response to Guion Miller when he needed additional information to process her claim.

|

| Eastern Cherokee application, Martha Rosana Brown, 2033 |

There are a couple of things on the 1835 roll concerning Gardiner Green that they did not know. First, his name is spelled incorrectly. The census taker left out the letter "I". After his name change to Gardiner Green, Young Wolf's name was always spelled with an "I" by the Moravians. Not one self proclaimed descendant spelled his name with an "I". Instead they spelled it exactly as it was recorded on the 1835 roll.

The other thing the claimants didn't realize is that Young Wolf lived on ROCK Creek, not Rocky Creek. The only record that lists him as living on Rocky Creek is the 1835 roll. The other records of him made during his lifetime list him as living on ROCK Creek. Again, it appears the self proclaimed descendants copied where he lived as it was recorded on the 1835 roll rather than actually knowing where he lived.

Clearly this Green family claim was not a legitimate claim.

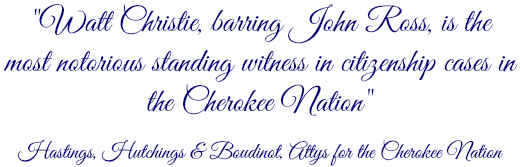

The Cherokee Nation attorneys correctly responded to the Green applicants' file with the following:

"Respondent not waiving his aforesaid demurrer, but insisting upon the same for answer to said application, says that Gardner Green through whom the petitioner claims to derive his right to citizenship in the Cherokee Nation, is not now, and has not been a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, since the removal of the said Nation, west to the Indian Territory as at present located and defined; that his name does not appear on any of the authenticated rolls of said Nation; that he nor any of his ancestors now reside, or ever have resided in the Cherokee Nation and Indian Territory, as citizens thereof."

|

| Squire Green et al, 1896 Citizenship application |

The Greens did not obtain their desired citizenship.

One might hope that would have been the end of it and Young Wolf could have been left alone to rest in peace. Sadly that is not the case. This is only the tip of the iceberg. Stay tuned for the next post about Young Wolf, his legacy, and what we can learn from it all.

Those are my thoughts for today.

Thanks for reading.

Click on images to enlarge.

For additional information on Young Wolf, Son of Mouse, please click here.

copyright 2018, Polly's Granddaughter - TCB

Tweet